Episode Transcript

Transcripts are displayed as originally observed. Some content, including advertisements may have changed.

Use Ctrl + F to search

0:02

Hold up. What was that? Boring.

0:05

No flavor. That was as bad

0:07

as those leftovers you ate all

0:09

week. Kiki Palmer here, and it's

0:11

time to say hello to something

0:13

fresh and guilt-free. HelloFresh. Jazz up

0:15

dinner with pecan, crusted chicken, or

0:17

garlic butter shrimp scampi. Now that's

0:19

music to my mouth. HelloFresh.

0:21

Let's get this dinner party

0:23

started. Discover all the delicious

0:26

possibilities at hellofresh.com. Hey.

0:31

I'm Ryan Reynolds recently I us Mint

0:33

Mobile legal team if big wireless companies

0:35

are allowed to raise prices due to

0:37

inflation. They said yes And then when

0:39

I asked if raising prices technically violates

0:41

those onerous to your contracts, they said

0:43

what the fuck are you talking about

0:45

you Insane Hollywood As so to recap,

0:48

we're cutting the price of Mint Unlimited

0:50

from thirty dollars a month to just

0:52

fifteen dollars a month. Give it a

0:54

try! Mint mobile.com/switch. Forty five dollars a front that humans

0:56

must have to the these permanent new customers for them to time unlimited

0:58

wasn't pretty good bye to come on South Pole! Turns out Mint mobile.com.

1:13

Opposite us rises the bulky form of

1:15

the Hulk painted black and

1:17

white and with her naked and

1:19

puny looking spars degraded to the

1:21

rank of clothes props for the

1:23

convicts. She stands in

1:25

curious contrast to the light steamers

1:27

that dance by her and little

1:29

sloops that glide like summer flies

1:31

upon the surface of the stream

1:34

almost under her stern through

1:36

broves of tumbled wheels and masses

1:38

of timber past great square buildings

1:40

from the roofs of which white

1:42

feathers of steam dart into the clear

1:44

air. We go forward to the water's

1:47

edge. A heavy mist

1:49

lies upon the marshes on the opposite bank of

1:51

the River Thames. The cold

1:53

gray light of early morning gives

1:55

to everything its most chilly aspect.

1:58

At 5 a.m. we step aboard. with the

2:00

determination of spending an entire day with

2:03

the Hulk's 500 and odd inmates. As

2:06

we run up the gangway of the

2:08

Silent Hull and survey the broad decks

2:10

in the misty light, the only sounds

2:12

heard are the gurgling of the tide

2:15

streaming past the sides of the black-looking

2:17

vessel and the pacing of the solitary

2:19

Waterguard. The Waterguard

2:21

proceeds to open the hatchways and we

2:23

descend, in company with him, to the

2:26

top deck in order to see

2:28

the men in their hammocks before rising for

2:30

their day's duties. The

2:33

hammocks are slung so close to one another

2:35

that they form a perfect floor of beds

2:37

on either side of the vessel, seeming

2:40

like rows of canvas boats. But

2:43

one or two of the prisoners turn on their

2:45

sides as we pass along the deck, and

2:47

we cannot help speculating as we go

2:49

upon the nature of the felon dreams

2:51

of those we hear snoring and half-moaning

2:54

about us. How many

2:56

are with their friends once more,

2:58

enjoying an ideal liberty? How

3:00

many are in acting or planning some

3:03

brutal robbery? How many

3:05

suffering in imagination the last

3:07

penalty of their crimes? How

3:10

many weeping on their mother's breast and

3:12

promising to abandon their evil courses

3:15

forever? And to how

3:17

many is sleep an utter blank? A

3:20

blessed annihilation for a while

3:22

to their lifelong miseries. Hello

3:30

and welcome to After Dark. I'm Maddy.

3:32

And I'm Anthony. And

3:50

today we're heading to the Hulks.

3:52

That is the grim floating prisons

3:55

that male convicts were sent to

3:58

as they were punished for their crimes. and

4:01

in some cases, awaiting transportation to

4:03

the colonies. To set the scene,

4:06

we just heard an account of a

4:08

visit to one of these ships by

4:10

the Victorian journalist and reformer, Henry

4:13

Mayhew. Our guide today to

4:15

the floating hells known as Prison Hulks is

4:17

Dr Anna McKay. Anna

4:19

is a historian at the University

4:22

of Liverpool, whose work focuses on

4:24

the experiences of prisoners across the

4:27

British Empire throughout the 18th and

4:29

19th centuries. Anna, welcome to After Dark.

4:32

Hello, thanks for having me. Wonderful to have you

4:34

here. Now, one thing

4:36

that I think we need to set out from

4:38

the beginning of this episode is

4:41

the difference between a prison hulk,

4:43

and we can talk a little bit about

4:45

what that is, what that looked like, and

4:48

convict ships in this period. Everyone knows

4:50

the stories of people who were convicted

4:53

of crimes and sentenced to

4:55

transportation to places like Australia.

4:59

But prison hulks are a slightly different beast. They

5:01

may look similar, but they do have a different

5:03

function, don't they? So can you tell

5:05

us a little bit about what a prison hulk is

5:08

and the difference between that and a convict ship? Yeah,

5:10

so like you say, we have like this big

5:13

story of Australia where, you know, it's

5:15

like the founding fathers of Australia are

5:17

a convict. They arrive on the first

5:19

fleet in the end of the 18th

5:21

century. But what prison hulks are is

5:24

they're the stage before transportation. So thousands

5:26

of men who were sentenced

5:28

to transportation would have experienced life on

5:30

board the hulks before they were then

5:32

transported to Australia. So the hulks are

5:34

a kind of like stepping stone in

5:36

this big process of transportation. And

5:38

they're really interesting because we kind of forget

5:40

about them in the story of Australia, the

5:42

story of British prisons. And they

5:44

were just experienced by tens of

5:47

thousands of men across the late 18th and 19th

5:49

century. I

5:51

was just going to say, Anna, if you can give us a sense of

5:53

what a prison hulk looks like. So it

5:56

is a ship, right? And what life would

5:58

be like aboard for some time? these prisoners?

6:00

What would the experience of selling foot on

6:02

a vessel like that be? Imagine

6:04

if you're sentenced to the dock in the

6:06

Old Bailey or standing there, you get seven

6:09

years by a judge. You're taken in a

6:11

chain gang down to the Thames and you

6:13

get taken by boat along the Thames down

6:15

to say Woolwich or Chatham or one of

6:18

these Royal Naval dockyards not too far from

6:20

London in lots of cases. You

6:22

arrive at the docks and there's

6:24

this big old ship. These prison

6:27

hogs were actually ex-naval ships about the

6:30

time. Things like HMS Victory that we

6:32

think about now, they actually

6:34

got converted after being in these

6:36

big naval battles. They were all

6:38

battle-scarred. Their hulls were blasted

6:41

open by cannons and their masts

6:43

and rigging had been removed. You're

6:46

taken to one of these things and you board the

6:48

decks and you go on board. You

6:50

basically live on board an old

6:52

ship for up to seven years.

6:54

Some people were there for months,

6:56

some people were there for years and that's just

6:59

your life. Instead of a prison system,

7:01

which we think about as being quite

7:03

regimented, basically a building that you would

7:05

live in, you're instead living on a

7:07

boat. It's creaky, it's

7:10

smelly. The air from the Thames

7:12

is disgusting throughout the 19th century.

7:15

You live on board, you sleep in a

7:17

hammock and every day you're rode out to

7:19

shore and you labour on the Thames or

7:21

you labour in the dockyards. What they're doing

7:23

there is they're building up fortifications.

7:26

They're cutting down timber and

7:28

they're basically human labour and

7:30

things like that. That's

7:32

what they're doing. A

7:34

lot of people might be familiar

7:36

with prison hogs from, say, Charles Dickens'

7:38

Great Expectations, where Pip is

7:41

slightly haunted by the presence of

7:43

this prison hulk that's waiting in

7:45

the near distance where Magwitch and

7:47

other convicts are held and escape.

7:49

This threatens their community. But

7:52

actually, this idea doesn't begin in the

7:54

19th century, does it? It has earlier

7:56

origins. The prison hulk systems came

7:58

into light in in 1776. So

8:00

we have the War of American Independence breaks out

8:03

in 1775. And prior to actually that

8:07

point in time, Britain had always transported

8:09

its convicts to the American colonies. So

8:11

like Maryland and the Chesapeake Bay and

8:13

places like that where they worked on

8:16

plantations, literally that's from like the 1718

8:18

Transportation Act is even further back than

8:20

that just kind of informally. So people

8:23

had always been transporting prisoners. But what

8:25

happens with the American War of Independence

8:27

is that suddenly the gates are closed

8:30

and there's no longer able to transport convicts and

8:32

basically get rid of them to America. So the

8:34

British government suddenly in this state of flux, you

8:37

know, what do we do? Our prisons are overcrowding.

8:39

Where should we put all our convicts? So they

8:41

suddenly just look around, they say, well, look, we're

8:43

in the middle of the Napoleonic Wars, you know,

8:46

and the American Wars, all these kind of global

8:48

wars are happening. There's loads of ships lying around

8:50

that have been battered and bruised in battles and

8:52

we don't know what to do with them. So

8:55

they just said, right, let's use these old ships.

8:57

So 1776, they start this thing called

8:59

the Hulk Act. And it's just a temporary

9:01

act. It's only supposed to last just a

9:03

few months because Britain assumed that they're going

9:06

to win the war with America and they

9:08

can just start transporting people back again. But

9:10

instead, what happens is that the Hulk system

9:12

works in England for about 80 years, it

9:14

goes on for ages and ages. And yeah,

9:16

just 10s and 10s of 1000s of people

9:18

pass through them over time. One

9:20

thing that always strikes me about prison hulks,

9:22

Anna, and I don't know how

9:25

much you kind of come across this in your research

9:27

is just how literate people were when it came to

9:29

ships and that actually a lot of people would

9:32

have spent time on ships, not

9:34

as criminals, possibly before they themselves

9:36

ended up in prison hulks. You

9:38

talked there about prisoners during

9:40

wartime being put into hulks. And

9:42

actually something that I researched in

9:44

my book was prisoners who had

9:47

been captured in the Caribbean in

9:49

the 1790s during the war between

9:51

Britain and France, who were then

9:53

transported to Britain to the

9:55

south coast to be prisoners of war. And

9:57

actually within that were

10:00

divided based on their racial identity.

10:03

And a huge portion, something like 2,500 prisoners, who

10:07

had been previously enslaved by the French in

10:09

the Caribbean, had been freed to fight the

10:11

British, captured by the British and brought over.

10:13

When they got to the South Coast, it

10:15

was the Black prisoners who were put onto

10:17

a prison hulk, and the white

10:19

prisoners were kept on the shore. And

10:21

you think there about the experience

10:24

of those individuals being

10:26

aboard, possibly ships that had taken

10:28

them during the slave trade to

10:30

the Caribbean, if they were first generation slaves,

10:32

often they would be second or third, or

10:34

even fourth generation, I suppose by that point.

10:37

Then on a ship, maybe during a

10:40

battle, during war, being captured in the

10:42

Caribbean, then coming across the Atlantic to

10:44

Britain, and then being put on a

10:46

prison hulk, that there's just

10:48

so much maritime experience, experience

10:50

of those sort of spaces,

10:53

those floating, claustrophobic, dark,

10:55

grimy, dangerous spaces, that

10:58

it's quite hard for us to

11:00

capture today, I guess, because a

11:02

lot of those environments don't exist

11:04

anymore. Obviously, prison hulks, maybe

11:06

with the exception. I think, did you mention the

11:08

victory was once used as a prison hulk, was

11:10

that right? Yeah, so the victory was used as

11:13

a prisoner of war hospital ship,

11:15

around the same time as your Portchester Castle

11:17

prisoners, actually. So they would have all kind

11:19

of been in the dockyard together. So yeah,

11:21

like we said, there's this big period of

11:24

warfare, but prison hulks are starting, and also

11:26

they're capturing prisoners of war overseas, and bringing

11:28

them back home. Even though you might get

11:30

captured in the Caribbean, you're somehow transported back

11:33

to England. Then you wait

11:35

to be exchanged, or you wait to be sent back, and

11:37

things like that. All of these

11:39

ships are all happening in the dockyards at exactly

11:41

the same time. I think that's so crazy, because

11:44

there's actually, I was thinking about it the other

11:46

day, there's this really cool quote from this woman

11:48

called Lady Jurningham in the 18th century. In

11:51

her diary, she writes that she went with her

11:53

son in just a small boat, and

11:56

they rode round Portsmouth together, and they

11:58

went to listen to... to all the

12:00

different voices of all the prisoners in the boats

12:02

that they passed by. So they're

12:04

actually rowing past the prisoner of warships and

12:06

they're saying, it's great because we can hear

12:09

all these Spanish and French voices. And it's

12:11

like Babel, all these chattering languages. And

12:14

then they go to the next ship, one

12:16

over, and it's a convict ship grated with

12:18

iron bars. So they're more heavily fortified, but

12:20

they're like, oh, look, there's convicts in this

12:22

one. And I just think that's crazy that

12:24

everyone's... Yeah, it's all happening at the same

12:26

time. We have all these flows across the

12:28

ocean of convicts. We have prisons of war.

12:30

We have enslaved people. And it's all

12:32

simultaneous. And I don't know, Britain's just

12:34

getting on with it at the same

12:37

time. I think it's that

12:39

layering, isn't it, of all those different

12:41

experiences and communities and the fact that

12:43

often those layers happen aboard the same

12:45

vessel if it's used as a warship

12:47

or as a ship to trade or

12:49

to transport enslaved people. And then it

12:51

has this other life as a prison

12:53

hulk. And just thinking

12:55

about that fantastic quote that you mentioned, that's

12:57

incredible. I've not actually come across that before.

13:01

How do you go about in

13:03

the archive accessing these spaces that

13:05

predominantly don't exist anymore? How do

13:07

you go about seeing what

13:09

that experience would have been like for people? It's

13:12

weird because when I started out, I thought, oh,

13:14

God, it's going to be really difficult finding the

13:16

voices of convicts because, like you said, can

13:19

they read? Can they write? Can they actually

13:21

record their own experience? But actually,

13:23

when you sort of read between the

13:25

lines of all those archival sources, you

13:28

could sit down in the archives and you could

13:30

look at a report that says, we have this

13:32

number of convicts today. So number one, you found

13:35

their names. And then number two, sometimes they say

13:37

how old they were. Sometimes they say they could

13:39

read or write. They actually record that because

13:41

they're interested in where the prisons are, literate

13:43

or not, because sometimes if you then get

13:45

transported to say to Australia, they're like, we're

13:47

interested in people who can read and write.

13:49

We need a clerk in our office. So

13:52

they're recording details about people. Sometimes

13:54

they even say they've got freckles.

13:56

They've got a broad chin and

13:58

things like that. saying that because if they

14:01

escape, they can find them again. They can say, we're

14:03

looking for a guy with blue eyes and blonde hair.

14:07

Or tattoos is another common one, of course. Yeah, I

14:09

love it when I find a convict with a tattoo.

14:13

Yeah, so you kind of begin to sift through

14:16

all this information. It's not nice, but

14:18

I was going to say, luckily for

14:21

me, there's a lot of records about

14:23

convicts out there because people were interested

14:25

in prisoners. If you

14:27

pass through an administrative process, whether that's a

14:29

poor house or a prison hulk or

14:32

even just a prison, someone's going to write your

14:35

name down. They're going to write your age down.

14:37

They might even record whether you've been badly behaved

14:39

or not, whether you tried to escape or whether

14:41

you got drunk. So through all of

14:43

that, and then you kind of go back to those, say, a

14:46

letter from an overseer that's written in Bermuda on

14:48

the hulk's air and they're complaining saying, excuse me,

14:50

all the convicts have got drunk, what do I

14:53

do? Then you can go, oh, wasn't there a

14:55

convict in Bermuda who was written down as drunk

14:57

that I've seen before? And you go back, you

14:59

cross-reference it. So you're kind of hopping between all

15:01

these different sources until you finally say, I think

15:03

that's the full story now. I think I've got

15:05

it all. So, Anna, if you

15:08

were unlucky enough to have

15:10

found yourself in one of these prison

15:12

hulks, what are the conditions?

15:14

What are the experiences? What are people

15:16

experiencing when they are confined in these

15:18

spaces? They're not very nice. You

15:22

have to compare them to what a prison

15:24

on land was like. So imagine going into

15:26

a cell in Newgate, how stinky

15:29

and overcrowded and busy and noisy

15:31

and just exhausting that is. Well,

15:34

put that onto a boat and

15:36

that's kind of what the hulks

15:38

were like. So yeah,

15:40

the conditions were pretty awful. Sometimes moored

15:42

up in mud, the Thames, the tides

15:44

of all the weather ships were moored

15:46

would kind of like, it gets stuck

15:49

in the mud. So that could be

15:51

really smelly. At the point in the

15:53

19th century, people still believed in miasmas.

15:55

So they would think that disease was

15:57

spread through this contaminated air. you're

16:01

living on board a convict ship and your toilet's

16:03

emptying out into this sludgy wasteland

16:06

below. Then you get TB.

16:08

Everyone's like, it's the hulks. The hulks have

16:10

caused this disease and cholera.

16:13

They get blamed for cholera and loads

16:15

of other diseases. But obviously, it's just

16:18

poor sanitation. Convicts are having

16:20

to drink the water from the tents, for

16:22

example, because it's not exactly clean now. But

16:24

imagine it in the 1830s. It's

16:26

not a great life. You're up at, say, 6

16:28

in the morning. You get rowed out to the

16:31

dockyards after your breakfast, which is not very filling

16:33

or nutritious. It's normally just a kind of mush

16:36

that they put together called

16:38

burgoo, which is a kind of

16:40

convict porridge, which I think is just like

16:42

bad grains. So you're given your bowl of

16:44

burgoo, and then you get in the boat

16:46

and you go out to labor in the

16:48

dockyards. There's tons of accidents.

16:51

Horses run away and timber falls down.

16:53

People get their hands

16:55

crushed. Someone in Bermuda

16:57

gets crushed by an anchor falling down into

16:59

the area where

17:02

he's working. Convicts are even working in

17:04

diving belts. So they're going underneath the

17:06

water to actually labor on parts of

17:08

the dockyard that you can't reach unless

17:11

you're underwater. So really high risk jobs.

17:13

It's kind of punitive as well. You're

17:15

being made to work hard

17:18

jobs because you're a prisoner. They're

17:20

kind of putting them to all the dirty work. And

17:23

so you get back at night, you're exhausted, and your

17:26

bones are aching. There's no bath or

17:28

anything. You're given another bowl of mush.

17:31

And then they say, right, it's time to do

17:33

your reading and writing now. So imagine

17:36

working for like 12 hours in the

17:38

dockyard and you come back home and

17:40

then they say, right, we're doing sums

17:42

today. Because in the 1820s, they started

17:44

to teach convicts how to read and

17:46

write because they thought, this is a

17:48

good reform. We're reforming people. We're teaching

17:50

them to read and write so that

17:52

when they go back into society, they're

17:54

better citizens. But it's exhausting. That's a

17:57

crucial difference, I suppose, between the 18th

17:59

and the 19th century prison hall. Obviously

18:01

in the 18th century, the prison system,

18:03

generally whether it's aboard a ship or

18:05

on land, is just

18:07

about removing that person from

18:09

society for a certain period of time

18:11

until they can pay their debt off

18:14

or until they go to the gallows

18:16

or are transported. But in

18:18

the 19th century, there is that reform

18:20

idea brought in, and this idea that

18:22

prison itself can be a transformative experience

18:24

and something that can make someone a better

18:26

person or a better citizen in society when

18:29

they come out of that. That's so fascinating.

18:31

The other thing that's really striking me, Anna,

18:33

while you're talking there is about the

18:35

fact that these people who are malnourished,

18:38

mistreated, they've had their two bowls of,

18:40

what did you call it? Bagu-y-mush-ya-bagu a

18:42

day, that they're existing

18:45

on these meagreations. And

18:47

yet during the day, they are helping

18:50

to build the infrastructure of

18:52

Britain, of its empire, the very

18:55

machinery and foundations

18:57

of what keeps the country going and keeps

18:59

it growing in the world and the

19:02

source of its international power. They

19:04

are part of that, but at night

19:07

they are removed back onto

19:09

the hulks. I wonder if you can maybe

19:11

speak a little bit about how

19:13

the hulks were perceived from the mainland

19:15

as well. You spoke about a woman

19:17

in the 1810s rowing

19:19

out to see the prisoners of

19:22

war in hulks and the convicts

19:24

in the neighbouring hulks. Is

19:27

there a sense that these are frightening

19:29

people who are offshore because they're not

19:31

fit to be with the rest of

19:33

society? Is there a sense that the

19:35

hulks are just mere convenience and they're

19:37

no different from maybe walking past some

19:39

big London prison like you mentioned Newgate

19:41

a moment ago? Do people

19:44

see them differently? Is there a fear about

19:46

them? Is there a resentment? Because they are

19:48

there on the horizon all the time. Yeah,

19:50

what's really interesting about the hulks, because

19:53

you can kind of track this change

19:55

or shift in opinion over time. So

19:58

sort of beginning at the hulks in the 17th century.

20:00

They're new, they're kind of

20:02

scary, they're weird on the landscape. So,

20:04

just imagine waking up in Woolwich and

20:06

looking out of your windows and seeing

20:08

this kind of big dirty ship full

20:10

of prisoners outside. So locals

20:13

did not like them. They complained they were

20:15

noisy and dirty. I mentioned they

20:18

kind of blame them for disease and local

20:20

sort of crime rates. People were always terrified

20:22

of an escaped convict. We see at the

20:24

start of great expectations. Everyone's like, right, he's

20:26

out. Let's go get him. Everyone

20:29

is scared of convicts. But

20:31

what's really interesting is over time it kind of

20:33

changes. So we go from this fear of the

20:35

convict. If you come into contact with one, you're

20:37

going to be like contaminated and you might even

20:39

turn into one yourself. You go

20:42

from that to then, you know, by the sort

20:44

of mid 19th century, people are starting to say,

20:46

hang on a minute, prison ships aren't as bad

20:48

as the people who were saying we should still

20:50

have them. So you get

20:52

to see like, you know, by the 1840s,

20:55

you know, it's a long time that they've been going, you

20:57

know, like 70 years. But

20:59

by that point, people are saying, I think

21:01

convicts are actually being quite hard done by

21:04

I don't think that we should be treating

21:06

them like this. And you start to see

21:08

people criticizing the system rather than being afraid

21:10

of the convict in newspaper reports. And I

21:12

just love that change in opinion. And I

21:15

kind of think that great expectations taps into

21:17

that because that was actually published in the

21:19

1860s and it's a bit later than the

21:21

convicts. But, you know, it's a historical novel

21:23

set in the Napoleonic era. So it's kind

21:25

of characterizing that fear that we see, you

21:28

know, in the 1770s and, you

21:30

know, Napoleonic era kind of hulks, scary

21:33

hulks. But then, you know, it's

21:35

almost like a thing of the past that he's

21:37

looking back and remembering them as bad, like

21:40

as almost as is to say, you know, we're different now.

21:42

We've moved on. Well, if you

21:44

were a convict on one of these

21:46

ships and now we've described how awful

21:48

the conditions were inhumane to some people,

21:50

even contemporaries, one way to

21:52

get off them was to be transported

21:54

and to, in some cases, take a

21:56

trip, let's say, to Australia. Could

21:59

you describe? for his and what that journey

22:01

might look like. What was the

22:04

process after which you're taken off the prison

22:06

hulk? What then begins to happen?

22:08

What's the next part of that journey? A

22:10

great journey of the convict. When you're, say, in

22:12

the hulks, they go around, they say, oh, he

22:14

looks strong, he looks fit, he's a good worker.

22:17

So you're immediately sort of singled out and they

22:19

put your name down and then they say,

22:21

right, we need 50 people for

22:23

the next convict ship. So you're taken off

22:25

board and you're put on board a convict ship.

22:29

So there's convict hulks and there's convict ships.

22:31

So you're taken on board a convict ship,

22:33

which when it reaches its full capacity, like

22:35

500 people. These are people

22:37

who aren't just male convicts anymore. So you've

22:39

got the male convicts from the hulks. They're

22:42

quite a big proportion of the convicts that

22:44

sail to Australia. But then you also have

22:46

female convicts who were just in prisons and

22:48

they've sort of been traveling down from wherever

22:50

their jails or prisons and lockups were. They're

22:52

traveling down the country to meet that convict

22:54

ship, say in Portsmouth, the port where it

22:56

sails from. So they're all on

22:58

board, right? And they're kind of segregated by

23:01

class and decks. So there's like,

23:03

say, three decks of a ship. They put

23:05

up some iron bars to separate the men

23:07

from the women. It's not just people roaming

23:09

around all the time and talking and gambling

23:11

and having sex and things. You're just, the

23:13

men and the women are separate. And then

23:15

you have sort of like militias and guards

23:17

who are on board to make sure you

23:19

don't get up to anything bad. And then

23:21

you set sail. So the journey takes a

23:23

couple of months. You go from, say, Portsmouth

23:25

or Plymouth, sometimes you stop off at Rio.

23:27

So you go all the way across the

23:29

ocean down to Rio, stop up and refuel,

23:31

get some more water, get some more food.

23:34

And then you go along the coast across

23:36

to, say, Cape of Good Hope in

23:38

South Africa and then straight to Botany

23:40

Bay in Australia. So that journey's, obviously

23:42

people are seasick, people are dying, people

23:44

are getting diseases. One of the things

23:46

that you see in, say, a surgeon's

23:49

log, they keep loads of records when you're on

23:51

board the convict ships and sailing as well. Certainists

23:54

are like, these people have got syphilis, everyone's dying.

23:56

People are coming on board with all these kinds

23:58

of diseases. because sometimes, you know, you're chosen for

24:00

being a good worker, sometimes they just want to

24:02

get rid of you. So, you know, they're like,

24:04

oh, God, get rid of that guy. He's been

24:07

with us for ages. So

24:09

they end up, you know, taking people

24:11

who, you know, might be unwell, on

24:13

board, people die still crowded. Disease spreads,

24:15

you know, on a ship. It spreads

24:17

in any close quarters. So, you know,

24:19

imagine that in the humid conditions of,

24:21

you know, sailing down the coast of

24:23

Africa. So it's not very pleasant. So,

24:26

Annette, the prisoners who have been transported

24:28

from the prison hulks to the convict

24:30

ships and they've done their journey, their

24:32

big epic journey. And if they've survived

24:35

that, they get to somewhere like Botany

24:37

Bay. What happens to them next? How

24:39

are they processed and how are they

24:42

integrated into what is already an established

24:44

convict society? Right. Yeah. So

24:46

once they arrive, male and female convicts are

24:48

basically sort of sorted out and

24:50

the women tend to go off into

24:53

say domestic service. So they become servants,

24:55

they become nursemaids and even they work

24:57

in factories and, you know, they sew

24:59

garments for the growing colony. And then

25:01

men tend to work in chain gangs.

25:03

So I mentioned that they were being

25:05

picked for being good laborers. Well, they

25:07

kind of know by now in the

25:09

colonies who's arriving and they say, right,

25:11

OK, where's our 50 men

25:13

who are good at working? So they kind of

25:15

pick up people and the convicts live in

25:18

this area called the rocks at the beginning in Sydney, which

25:20

is just a sort of like a rough

25:22

and ready convict settlement. And, you know, they live

25:24

in their own houses. They share them with other

25:26

people, but they go off to work every day.

25:29

And come back home at night. And you'd

25:31

think they have a little bit more freedom, as

25:33

opposed to say that life on the hulks, which

25:35

is really regimented. But you are still like an

25:38

unfree worker. You're not allowed to leave. If you

25:40

are, you get punished. Ryan

25:55

Reynolds here from Mint Mobile. With the price of

25:57

just about everything going up during inflation, we thought

25:59

we'd bring our prices down. So to help us,

26:01

we brought in a reverse auctioneer, which is apparently

26:03

a thing. Mint Mobile Unlimited Premium Wireless! Having to

26:06

get 30, 30, better get 30, better get 20,

26:08

20, 20, better get 20, 20, better

26:11

get 15, 15, 15, 15, just

26:13

15 bucks a month? Sold! Give

26:15

it a try at mintmobile.com/switch. $45

26:18

up front for three months plus taxes and fees. Promote

26:20

for new customers for limited time. Unlimited more than 40

26:22

gigabytes per month. Slows. Full terms at mintmobile.com. Hold

26:28

up. What was that? Boring. No

26:30

flavor. That was as bad as

26:32

those leftovers you ate all week.

26:34

Kiki Parma here. And it's time

26:36

to say hello to something fresh

26:38

and guilt-free. Hello Fresh. Jazz up

26:40

dinner with pecan-crusted chicken or garlic

26:42

butter shrimps can be. Now that's

26:44

music to my mouth. Hello Fresh.

26:47

Let's get this dinner party

26:49

started. Discover all the delicious

26:51

possibilities at hellofresh.com. Ryan

26:56

Reynolds here from Mint Mobile. With the price

26:58

of just about everything going up during inflation,

27:00

we thought we'd bring our prices down. So

27:03

to help us, we brought in a reverse auctioneer, which is apparently a thing. Mint Mobile

27:05

Unlimited Premium Wireless! Have it to get 30, 30, a bit to get 30, a bit

27:07

to get 20, 20, a bit to get 20, 20, a bit to get 20, a

27:09

bit to get 20, a bit to get 20, a bit to get 20, 20, a

27:11

bit to get 20, a bit to get 20, 20, a bit to get 20, a

27:13

bit to get 20, 20, a bit to get 20, a bit to get 20, a

27:15

bit to get 20, a bit to get 20, a bit to get 20, 15, 15,

27:17

15, just 15 bucks a month. Sold! Give it a try at mintmobile.com/switch. $45

27:19

upfront for three months plus taxes and fees. Prom or eat

27:21

for new customers for limited time. Unlimited more than 40 gigabytes

27:23

per month. Slows. Full turns at mintmobile.com. So

27:35

we've established that one way to get off

27:37

a prison hulk is to go to Australia,

27:40

say. Another way would

27:42

be to die, which is going

27:44

to take us to our next narrative. In

27:51

May 1846, the convict Henry Driver

27:54

was admitted to the hospital on board

27:56

the prison hulk warrior. Within

27:58

five days of arriving in the prison hulk, the hospital was Hulks

28:00

Hospital and being placed under the care

28:02

of the chief surgeon, a man called

28:04

Peter Bossie, Henry Driver was dead. We

28:08

are told that this unhappy wretch

28:10

had no sooner departed this life

28:12

than the body, still warm, was

28:14

carried over to the dead house

28:16

and the surgeon's knife was at

28:18

work opening and dissecting. Entrails

28:20

taken from the body were thrown into

28:23

the river where dozens had gone before.

28:26

It was an open-air spectacle, visible

28:28

to not only convicts on the

28:31

warrior, but inmates on other hulks

28:33

moored nearby. A

28:35

man on a neighbouring ship remembered how

28:38

a lot of thick blood came over the

28:40

side of the ship and the

28:42

entrails hung where the ears of the bucket are

28:44

put on and a medical

28:46

officer took and shook the bucket and

28:48

shook them off and it was enough

28:50

to make anybody's blood run cold to

28:53

look at it. Well,

28:59

we've talked about the Thames being

29:02

not great drinking water and I think that's

29:04

fair evidence of that. Anna,

29:06

tell us about what turns out to

29:09

be the convict corpse scandal as it's

29:11

known. How does that play out? Obviously,

29:14

we've got huge transgressions in terms of

29:16

the space of the prison hulk here,

29:18

the treatment of prisoners alive

29:20

and dead. How does that play out and

29:22

how does it lead eventually to the demise

29:25

of the hulks? This

29:27

story is so interesting. Basically, what happens

29:29

is a convict who's on the same

29:31

ship as Thomas Driver, he actually writes

29:33

to a local MP. He

29:35

says, look, there's some really bad goings on

29:37

on board the hulks and I'd like someone

29:39

to come and look into it. The

29:42

MP stands up in Parliament and he says, look, I think

29:44

we should go and check this out. There's

29:47

a small flurry of interest, shall we say,

29:49

in the newspapers and it adds a bit

29:51

of public pressure to the people in Parliament. They

29:53

say, all right, yeah, we'll commission an inquiry. They

29:56

send someone from the prison inspectorate, which is this

29:58

big public... body that looks

30:01

after all the prisons in the UK,

30:03

apart from the prison hulks. Because at

30:05

that point in time, prison hulks still

30:07

exist outside this bigger system of British

30:09

prisons. And that's what's kind of wrong

30:11

about them. Anything that isn't sort of

30:13

centrally managed can actually then be subject

30:15

to a bit of corruption, shall we

30:18

say. This prison inspector, it goes down

30:20

and he interviews 98 convicts

30:22

and overseers and guards. It's a really,

30:24

really thorough inquiry. And he says to

30:26

people, what's it like living on board

30:28

these hulks? Are there problems

30:30

with these medical abuses? And then he

30:32

starts to learn the story of Peter

30:35

Bossie, who, he's a member of the

30:37

College of Surgeons. He's an upstanding member

30:39

of community. He has a doctor's surgery

30:41

in Woolwich that he has with his

30:43

brother. But it turns out that Peter

30:45

Bossie, the surgeon, is actually using

30:47

the hulks almost as a sort of training school

30:50

for his doctor's surgery. So he's getting

30:52

all of his apprentices to come round on the

30:54

hulks every day. He's not supposed to be doing

30:56

that. He gets them to all come

30:58

on board and they go round like it's a

31:00

teaching hospital. So Bossie has this stick that he

31:02

uses to sort of tap the convicts on the

31:04

head every morning and say, how are you doing,

31:07

my fine fellow and things like that. And everyone's

31:09

like, this is insulting and it's weird. So,

31:12

you know, the prison inspector are learning these kinds

31:14

of things. They're writing it all down and, you

31:16

know, they're making a few assumptions. And so they

31:18

ask about the body of Thomas Driver and they

31:20

say, what actually happened with him? And

31:23

they say, well, he died. And

31:25

the laws of the anatomy

31:27

act that happened in the 1830s, 1832,

31:29

that comes about and it says you

31:31

must not dissect a body within

31:34

48 hours. You have to do 48 hours

31:36

waiting time before you then dissect a body

31:38

or else it's illegal. And so the convicts

31:41

on board the warrior hulk in Woolwich were

31:43

saying they dissected him way earlier than 48

31:45

hours. They think that it was illegal. So

31:47

they investigate that. Turns out it

31:50

wasn't illegal. Turns out they did wait. But

31:52

what actually happens is they realize that the people who

31:54

are all the medical men on board the hulks are

31:57

actually just using them as kind of to do experiments

31:59

and You know, they mentioned that someone had the head

32:01

of a convict in a bucket that they were going

32:03

to give to a friend in Maidstone in Kent. And

32:06

it's all these kind of, you know, you should not

32:08

be doing that kind of things. And

32:11

they keep finding out, you know, the convicts who

32:13

were in charge of like cleaning up the death

32:15

houses after a convict's been dissected, they might be

32:17

the friends of another convict who, you know, had

32:19

died. And so there's all these kind of like

32:21

morally wrong things that are happening on board the

32:23

hulks. And they find out that

32:25

the people in charge on board these hulks

32:28

are actually dissecting the convicts bodies themselves just

32:30

to determine the cause of death. But when

32:32

they're being sent to the anatomy schools, the

32:34

anatomists are saying, we can't actually work with

32:37

these bodies. They're too mangled or broken. And

32:40

so what happens in the end is they condemn

32:42

the system. They say this is shouldn't

32:44

be happening. And they say Peter

32:47

Bossey needs to be fired and removed from the

32:49

hulks immediately, which he is. And they

32:51

also find out that the person who's in charge of the

32:53

hulks, who's a man who used to

32:55

work in the home office, he's a clerk called John

32:57

Henry Kapper. They find out that he's so old and

33:00

infirm because he's actually been in charge of the hulks

33:02

for about 60, 40, 60 years by then. They

33:05

find out that his nephew, who is

33:07

a green grocer, has actually been running the

33:09

hulks on his behalf. And so they say,

33:11

right, we need to overhaul this system. So

33:13

what they do instead is finally the hulks

33:15

come under the control of the prison inspector.

33:18

Now they're, you know, managing big prisons like

33:20

Pentonville, Newgate, Milbank, all these ones that are

33:22

working a little bit better than the hulks.

33:24

Like no prison in the 19th century is

33:27

good. Let's just say that. But like these

33:29

ones are working more functionally,

33:31

should we say. And so what happens is

33:33

they underneath the charge of these people who

33:35

are like more, you know, enlightened about how

33:38

a prison should be run, the hulks eventually

33:40

closed down. But that's a real watershed moment,

33:42

that moment in 1847, that inquiry, where they

33:44

realized that the hulks and the bodies of

33:47

the convicts have been abused by the people

33:49

in power. And so this inquiry takes place

33:51

in 1847, but it's not for another 10

33:54

years, 1857, right,

33:57

where the prison hulks are actually

34:00

decommissioned. What happens in that intervening

34:02

decade to ensure that that sparks

34:05

the end of these hulks? Well,

34:08

now that the prison hulks are

34:10

under the purview of the prison inspector, these kind

34:13

of men who are in charge can see

34:15

that they're not working. They say, look, people

34:17

are dying on board. The Russians aren't

34:19

as good. Convicts don't like being

34:21

on the prison hulks as much as in other

34:23

prisons. No one likes being in prison, but again,

34:25

the hulks aren't good. In those

34:27

10 years, the prison inspector slowly

34:29

wind the system down. What used

34:32

to happen when you've got a hulk,

34:34

if it's too old and too battered,

34:37

so battered that even the walls are

34:39

falling apart, so some convicts, they escaped

34:41

literally by leaning against the rotten walls,

34:43

which are saturated with filth and old

34:45

water. You could actually kind of push

34:47

your way through the rotten wood in

34:49

some cases. What used to happen was

34:51

they just get a new hulk. They'd

34:53

say, right, let's go to the Admiralty.

34:55

Let's buy an old ship, something

34:58

that's a reasonable condition that we can use for,

35:00

say, 30 years to house convicts. They stopped doing

35:02

that. They said, look, when one ship is old

35:04

and it can't be used anymore, let's just get

35:06

rid of it. Let's break it up. They untangle

35:09

it all and sell whatever bits

35:11

and bobs they can to make

35:13

a little profit. That's it. You

35:16

start to see a decline in

35:18

actual numbers of hulks. Also, what

35:20

happens is they say, let's put

35:22

more prisons close by. Say, Chatham,

35:25

convicts on the hulks start to build

35:27

a prison on land. They do that

35:30

in Portland too, near Dorset. They're starting

35:32

to actually build their own prisons. They're

35:34

gradually being moved off and those ships

35:37

can be decommissioned as there's fewer and

35:39

fewer and fewer convicts. There's

35:41

also less of a need to actually

35:43

have convicts on prison hulks anymore because

35:45

they're no longer transporting people to Australia.

35:47

There's a real decline in the numbers

35:49

of people who are being sent to

35:51

Australia. From, say, the 1830s,

35:54

there's huge debate sparking up in parliament

35:56

about whether we should keep transporting people.

35:58

There's all these kinds of factors. Hi,

41:24

this is Craig Robinson from

41:26

Ways to Win, and support

41:28

for this podcast comes from

41:30

Invesco QQQ. Invesco QQQ is

41:32

proud to sponsor this episode

41:34

and even prouder to provide

41:37

access to innovation for the

41:39

last 25 years. Basketball has

41:41

had innovations over the years

41:43

too. We're seeing the game

41:45

played in new ways every

41:47

day. Learn more at invesco.com/QQQ.

41:49

Let's

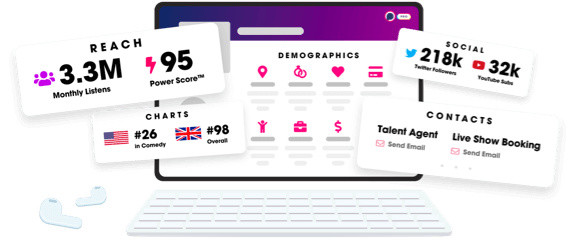

Unlock more with Podchaser Pro

- Audience Insights

- Contact Information

- Demographics

- Charts

- Sponsor History

- and More!

- Account

- Register

- Log In

- Find Friends

- Resources

- Help Center

- Blog

- API

Podchaser is the ultimate destination for podcast data, search, and discovery. Learn More

- © 2024 Podchaser, Inc.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

- Contact Us