Episode Transcript

Transcripts are displayed as originally observed. Some content, including advertisements may have changed.

Use Ctrl + F to search

0:00

To make switching to the new Boost

0:02

Mobile risk free, we're offering a 30-day

0:04

money-back guarantee. So, why wouldn't you switch from

0:06

Verizon or T-Mobile? Because you have nothing to lose.

0:08

Boost Mobile is offering a 30-day money-back

0:10

guarantee. No, I asked why wouldn't

0:12

you switch from Verizon or T-Mobile. Oh.

0:14

Wouldn't. Uh, because you love wasting

0:17

money as a way to punish yourself because

0:19

your mother never showed you enough love as

0:21

a child? Whoa, easy there. Yeah.

0:23

Applies to online activations, requires port-in

0:25

and auto-pay. Customers activating in stores

0:27

may be charged non-refundable activation fees.

0:30

Welcome, friends, to the playful scratch from

0:32

the California Lottery. We've got a special guest

0:34

today, the Scratcher Scratchmaster himself, Juan. Juan, you've

0:37

mastered 713 playful ways to scratch. Impressive.

0:40

How'd you do it? Well, I began with

0:42

a coin, then tried a guitar pick. I

0:44

even used a cactus once. I can scratch

0:46

with anything. Even this mic right here. See?

0:50

See? There you have it. Scratchers are fun no

0:52

matter how you scratch. Scratchers from the California Lottery,

0:55

a little play can make your day. Please

0:57

play responsibly. It must be 18 years or older to purchase

0:59

player claim. Welcome

1:08

to Echoes of History, the place to

1:10

explore the rich stories from the past

1:12

that bring the world of Assassin's Creed

1:14

to life. I'm Matt Lewis. In

1:17

this sequence of episodes, we've taken a

1:19

trip across the Atlantic to revolutionary America,

1:21

where the 13 colonies

1:23

struggled for independence from British

1:25

rule. Assassin's Creed 3

1:28

offers players a glimpse into the room where

1:30

it happened, the signing of

1:32

the Declaration of Independence. But

1:34

what was the Declaration? Was

1:37

it more than just a document? Who wrote

1:39

it? And what were the

1:41

immediate and lasting ripples of

1:44

making such a declaration? Late

1:50

morning sunshine streams through the windows,

1:52

softly lighting the hall. It's

1:55

the height of summer in the year 1776 and the room

1:57

is... full

2:00

of delegates who have convened

2:02

here in Philadelphia from across

2:04

the 13 colonies of America.

2:07

Although not everyone from across the colonies

2:10

are present today, over

2:12

the coming weeks 56 representatives will

2:14

sign their name to a document

2:17

lying on the centre of the

2:19

table. The

2:22

document that represents the birth of

2:24

a new nation, an

2:26

independent nation. You

2:29

hover unnoticed in a darkened corner,

2:32

watching as the delegates and other members

2:34

of the Congress talk quietly to one

2:36

another in small groups around the room.

2:39

Gathered where the American Declaration

2:41

of Independence lies, stand

2:43

three men. Your

2:46

closeness to them gives you a thrilling shiver.

2:49

You know who they are. Know

2:51

that the document on the table was drafted

2:53

by them and that it's

2:56

their soaring rhetoric that will

2:58

embolden everyone here in

3:00

their shared mission. One

3:03

man stands taller than the others, his hair

3:05

bound at the back of his neck in

3:07

a graceful ponytail. His face

3:09

is drawn with an obvious lack of

3:11

sleep. He spent many a restless night

3:14

considering what has to be written here,

3:16

but his eyes are bright with the

3:19

feverish energy of the gathering. He

3:22

is Thomas Jefferson and he

3:24

alone catches you looking at him

3:26

from across the room, returning your

3:28

curious gaze with a slight incline

3:30

of his head. The

3:33

70 year old Benjamin Franklin, his

3:36

spectacles perched low on his nose,

3:39

stands beside him and a

3:41

third man, shorter than Jefferson, speaking

3:43

quietly to his companions you

3:46

recognize as John Adams. The

3:49

quill pen is not picked up lightly by the

3:51

signets. The hall grows

3:53

pensive and silent as

3:55

the first names are called to sign

3:58

the declaration. It

4:00

is an act of high treason. With

4:03

this document they dissolve the colonial bonds

4:05

with Britain to their king

4:07

far across the Atlantic. Each

4:11

man in turn approaches the desk where John Hancock

4:13

sits. He is the

4:15

president of this constitutional congress and

4:17

his face is grave. He

4:20

gestures for the delegates to take the heavy

4:22

pen from its ornate silver inkstand and

4:25

in turn they sign the

4:27

declaration. When

4:29

it seems everyone present who will sign

4:31

has done so, you slip

4:33

through the gathered men, making your

4:36

way to the table at the hall's

4:38

centre. You look down

4:40

at the treasonous parchment stretched out on the

4:42

desk in front of you. At

4:44

the page's bottom it's filled with

4:47

scrawled signatures. You read

4:49

the elegant swirls of John Hancock

4:51

in the centre. You see Jefferson's

4:54

and other familiar names below. The

4:57

declaration itself is made up of line

4:59

upon line of neat cursive script

5:02

detailing the rights and

5:04

freedoms of this new nation.

5:07

Your gaze fixes on several

5:09

stirring lines in particular and

5:12

the gentle chatter of the room falls

5:14

away as you read, We

5:17

hold these truths to be

5:19

self-evident, that all men are

5:22

created equal, that they are

5:24

endowed by their creator with

5:26

certain unalienable rights, that

5:29

among these are life,

5:31

liberty and the pursuit

5:34

of happiness. To

5:39

find out more about the Declaration of

5:41

Independence I'm joined by Frank Colleono, Professor

5:44

of American History at the University of

5:46

Edinburgh. His latest book about

5:48

George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, a

5:50

revolutionary friendship, has just been published

5:52

by Harvard Press and can be

5:55

purchased from bookstores as an e-book

5:57

or an audiobook. Welcome

5:59

to Echoes of History. Frank. Thank you,

6:01

Matt. I'm really looking forward

6:03

to this because I generally I'm

6:05

at home in the medieval period

6:07

and in Europe. So this era

6:09

of American history is something I

6:11

know very little about. And what

6:14

I do know is largely based

6:16

on the musical Hamilton. So please

6:18

don't shoot me, but that's the limit of my knowledge.

6:21

Come on in the water's warm. I think Hamilton's

6:23

great. It's engendered so

6:25

much interest in the period. It's wonderful.

6:27

So yeah, that's great. Perfect. We're still

6:30

friends. I wonder if you could just

6:32

set the scene for us a little bit in

6:34

terms of when are we and in

6:36

the build up to the Declaration of Independence,

6:39

what is happening in America? Okay, that's a

6:41

small question. Thanks, Matt. We'll start

6:43

off easy and we'll build up from there.

6:46

So what you need to know is in

6:48

the summer of or the spring and summer

6:50

of 1776, Britain and the

6:53

colonies or the 13 colonies in North

6:56

America that were rebelling against Britain,

6:58

had already been at war since

7:00

April of 1775. So the war

7:02

broke out in Massachusetts with the

7:04

fighting at Lexington and Concord outside

7:06

Boston in April of

7:08

1775. At that point,

7:10

the grand eloquently named

7:13

Continental Congress assumed governmental powers for

7:15

these colonies, these rebellious colonies. And

7:17

Congress met in Philadelphia, but it

7:20

wasn't really a government. And there's

7:22

this kind of weird liminal period

7:24

that goes on for 14 months

7:27

when the colonies and Britain are waging

7:30

war against each other, but the colonies

7:32

haven't yet declared independence. So for example,

7:34

some of the troops besieged, what happened

7:36

was there was fighting outside of Boston

7:39

in April of 1775. Colonial

7:42

militia besieged the British

7:44

troops in Boston from April of 1775 until

7:46

March of 1776. Some

7:49

of those colonial militia claimed to be laying

7:51

siege to British troops in Boston in the

7:54

name of the king. So it's if

7:56

you follow me, so it's a weird, there's a

7:58

weird kind of period. of slightly

8:01

more than a year when the

8:03

colonies are rebelling and they are

8:05

doing so, they claim to defend

8:07

their rights and liberties, but their

8:09

status is unclear. And in the

8:11

spring of 1776, Virginia,

8:13

which is the largest colony, and it's the

8:16

largest geographically, but it's also the largest in

8:18

terms of its population and economic might, calls

8:20

in early May of 1776, submits a resolution

8:24

to Congress asking

8:26

for a Declaration of Independence. And

8:29

so that's the immediate backdrop. I should also

8:31

say, and I'm sorry to go on at such length,

8:33

that in the intervening months

8:35

between Lexington and Concord in April

8:37

of 1775 and the formal Declaration

8:40

of Independence adopted by Congress on

8:42

July 4th, 1776, British

8:44

rule and government had broken down across

8:46

the colonies to a large extent, and

8:48

the colonies began kind of de facto

8:51

governing themselves to a large extent. So

8:53

some historians have argued there were a

8:55

series of declarations of independence when colonists

8:58

took on this kind of authority to

9:00

govern themselves. Yeah, very interesting. We've looked

9:03

at the kind of battles of Lexington and

9:05

Concord as the beginning of the revolutionary

9:07

movement, the desire to separate from Britain.

9:09

And I was interested in why it

9:11

took a year, why you've been at

9:13

war for a year before there is

9:15

a decision to move towards a Declaration

9:17

of Independence. So is that about getting

9:19

it more on a legal footing and

9:21

perhaps being a bit clearer about exactly

9:23

what it is you're fighting for? There's

9:26

a little bit of that. There's also the fact

9:28

that not everybody wants to declare independence, even those

9:30

people who are resisting British

9:33

rule, you know, the phrase they use

9:35

all the time. And I say this

9:37

mindful of the fact that I'm sitting

9:39

in Scotland right now, but they talk

9:41

about the rights of Englishmen, right? And

9:43

they talk about they believe these American

9:45

colonists, at least those who are free,

9:47

believe that they have the rights of

9:49

Englishmen. And so they're reluctant to sever

9:51

that tie in the decade between the

9:53

adoption of the Stamp Act, which started

9:55

this whole mess in 1765 and the

9:57

fighting at Lexington and Concord, polemicists and

10:00

Activists have made the case against

10:02

parliamentary rule quite extensively, but they

10:04

haven't gone after the king. And

10:07

they've maintained that they were actually

10:09

loyal for a decade. And so

10:11

it's a big step to declare independence and many

10:13

of them aren't ready to do that. Also,

10:16

you've got to bear in mind, the population,

10:18

John Adams, one of the leading patriots, famously

10:20

said the population was divided into thirds. One-third

10:23

patriot, that is supporting independence, one-third

10:25

loyalist, that is supporting the British,

10:27

and one-third neutral. The

10:29

proportions are probably off, his proportions are

10:31

off, but those are the main categories

10:33

of the population. Not everybody supports independence,

10:36

so it's going to

10:38

take them a while to get there. And

10:40

presumably, there are a group of people at

10:42

this Continental Congress who begin

10:44

to formulate the ideas of what

10:47

a declaration of independence might look

10:49

like. Presumably, this is a novel

10:51

idea. How do they go

10:53

about gathering the ideas that will be included

10:55

in the Declaration of Independence and what kind

10:58

of people are involved in that decision making?

11:01

So the Congress itself,

11:03

unsurprisingly, is comprised of

11:05

leading political figures from each of

11:08

their respective colonies. And

11:10

so these are men of wealth and

11:12

means, and many of them are slaveholders,

11:15

for example, including Thomas Jefferson, who will

11:17

be the main author of the Declaration

11:19

of Independence. What happens is,

11:22

once Virginia submits its resolution

11:24

calling for Congress to vote

11:26

on independence, Congress takes a

11:28

number of steps. It forms

11:30

a committee to start preparing

11:32

a declaration. It also

11:34

has committees to wage war and to

11:37

draft a new constitution for these colonies

11:39

once they become independent, etc. But

11:42

it also starts, there's a lot

11:44

of politicking going on because they

11:46

recognize that for such a momentous

11:48

step, the way voting was done in Congress then,

11:50

we use the word Congress and we talk about

11:52

Congress in the United States today, but it's not the

11:55

same thing. So voting

11:57

in the Continental Congress was done by

11:59

colonies. So each colony had one vote.

12:02

Didn't matter how large their delegation was. And

12:05

the congressmen recognized that for

12:07

a step as momentous as

12:09

declaring independence, they needed to

12:11

be unanimous. It wouldn't

12:14

be enough to have a seven to six

12:16

vote because that would signal that the colonies

12:18

weren't united in this

12:20

cause. They wanted it to be a unanimous vote. So

12:22

there's a lot of politicking going on in May

12:25

and June, especially in June of 1776. Meanwhile,

12:29

however, in anticipation of

12:32

declaring independence, they

12:34

established a committee that has

12:36

the so-called committee of five

12:38

to start drafting the declaration.

12:42

And so they're preparing for a declaration even

12:44

before they've even voted on it, if that

12:46

makes sense. And congress has issued over the

12:48

course of its previous meetings in the previous

12:50

year, it had issued a number of declarations

12:53

and statements that have been drafted by committee.

12:55

So there was some precedent for this. I

12:57

love drafting things by committee, such a great

12:59

experience. Yes, yes, and what

13:02

you'll know, what do they do? They

13:04

give the job to the most junior

13:06

member of the committee, which was Thomas

13:08

Jefferson. So there are five people on

13:10

this committee, John Adams of Massachusetts, Benjamin

13:12

Franklin of Pennsylvania, excuse me, Roger Sherman

13:14

of Connecticut, and Robert Livingston of New

13:16

York and Thomas Jefferson of Virginia. Jefferson

13:19

had a reputation as a writer, but he's also

13:21

the junior guy on the committee. And I think

13:23

that we know how committees work. You

13:26

do this, you start drafting the text. Has there ever

13:28

been a school or work project where there weren't four

13:30

people that did nothing and one who does all the

13:32

writing and all the work and carries everybody else? No.

13:36

I suppose the only benefit for Thomas Jefferson is

13:38

that he then gets attached to an enormously significant

13:41

document, which probably makes him more prominent than the

13:43

rest of the people in the group say, maybe

13:45

he doesn't do too badly out of it. That's

13:47

right, that's right. And is

13:49

there anything in particular that kind of

13:51

qualified those five men to get in

13:53

that room and put that together? Because

13:55

presumably no one has experience of declaring

13:57

independence. So this is something new. Nobody

14:00

has experience declaring independence. They are

14:03

all prominent people in their respective

14:05

colonies, some states. Some,

14:07

you know, Benjamin Franklin is a, if

14:09

he's not a globally known figure, he's

14:11

certainly a transatlantic figure of some renowned,

14:14

you know, both as a scientist and as a political

14:16

figure. Adams is a leading figure

14:18

from, of the, helped lead the Patriot resistance

14:20

in Massachusetts in the run up to the

14:23

revolution. So these are pretty significant figures in

14:25

their, in their own rights, some considerably so.

14:27

I mean, Franklin, as I say, is probably

14:29

the most well-known person on that committee when

14:32

it was formed. The thing to bear in

14:34

mind is that Congress has dozens of committees.

14:36

They're doing all kinds of stuff. They're waging

14:38

war. They're trying to establish diplomatic relations. So

14:41

there are lots of committees and lots of

14:43

opportunities for people to serve on committees. But

14:46

Jefferson in particular is chosen because

14:48

he'd been the author of a

14:50

pamphlet, which was published in 1774,

14:53

called A Summary View of the Rights of British America,

14:56

which is one of the most famous pamphlets in

14:58

the run up to the war,

15:00

the American War of Independence. And it's

15:03

a very eloquent and radical summation of

15:06

what would be called, I guess, the Patriot position as

15:08

of 1774, 1775. So

15:11

he came to Congress with some renowned

15:13

as a writer. And so

15:15

I think he's chosen, you know, Virginia has

15:17

to be represented on this committee because Virginia

15:19

is such an important colony. But also he

15:21

is the guy in the Virginia delegation who's

15:24

got a reputation as a writer. Yeah. So

15:26

I suppose in the absence of being able

15:28

to Google someone who can draft you a

15:30

Declaration of Independence over the Internet, what you

15:32

do is find someone who's done something fairly

15:34

similar, who's sort of justified the cause eloquently

15:37

previously and set him to work on

15:39

it. That's right. And he

15:41

was the main author, along with another

15:44

guy named John Dickinson, of a declaration

15:46

that Congress issued the previous summer, called

15:49

the Declaration of the Causes and Necessity

15:51

of Taking Up Arms, which was justifying

15:53

the armed resistance to Britain. So he

15:55

had some form there. And what were,

15:57

as they're drafting this document, what are

15:59

the the fundamentals? the core messages within

16:01

the Declaration? What is it setting out

16:04

to achieve? Well, this is a

16:06

really important question, Matt. It's a document that's

16:08

trying to do several things. First,

16:11

it is, as the document says,

16:14

it is announcing to the world,

16:16

we're here. There's a

16:18

new country, or there's... It's

16:21

a political statement.

16:24

But it's also intended as

16:26

propaganda. It's intended to help

16:28

mobilize the patriot resistance

16:31

to Britain. It's trying to lay

16:33

out in clear terms what this

16:35

struggles about. Crucially, though, it's also

16:37

a diplomatic statement. It is saying

16:40

to the world, but particularly to

16:42

the great powers of Europe, especially

16:44

France, that we are

16:46

not going back. Because

16:49

the French had provided kind of covert

16:51

assistance to the American rebels because they're

16:53

still upset about the outcome of the

16:55

Seven Years' War. But they're not going

16:58

to risk war with Britain if

17:00

the colonists, who historically had

17:02

always fought against France with Britain, are

17:05

going to patch things up with Britain and then turn on them. And

17:08

so that's the worry at Versailles.

17:11

And so the Declaration of Independence

17:13

is a statement and a signal

17:15

to European powers, especially France.

17:17

We are not going back. This is

17:20

not going to be like the Jacobite

17:22

rising. We're not going to be kind

17:24

of suppressed. We are declaring independence, and

17:26

therefore we are open for business. And

17:29

please enter into diplomatic relations with us.

17:31

And that will be important. France, of course, will

17:34

ally with the new United States in 1778. But

17:37

also it's crucial because it opens

17:39

up the coffers of Dutch banks

17:42

in particular, so that the Dutch

17:44

and bankers in the Netherlands will

17:46

also help finance the revolution after

17:48

the Declaration of Independence. So it's

17:50

got multiple purposes. It's a political

17:52

and philosophical statement directed at

17:54

Britain primarily. It's a

17:57

piece of propaganda intended to mobilize.

18:01

resistance to Britain within those

18:03

13 rebellious colonies, and

18:05

it's a diplomatic statement. Does the

18:07

document itself make an effort to

18:09

justify independence? Does it give reasons

18:11

why they want to be separate

18:14

from Britain? Yes, yes. So what

18:16

most listeners, if they know the Declaration of Independence,

18:18

they know the opening. They know the statement that

18:21

all men are created equal and endowed by their

18:23

creator with certain inalienable rights, and that among

18:25

these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,

18:27

right? That's the money shot. That's the mission statement

18:29

of the United States. However,

18:32

the bulk of the texts consists

18:34

of a long list, I think

18:36

there are 27 of them, charges

18:38

against George III. And

18:41

these are the things that often don't get read on

18:43

the Fourth of July in the United States, because it's

18:46

a relatively long document. And

18:48

those are incredibly important, I think, because

18:50

they're making the case for severing

18:53

that tie with the crown,

18:55

with the monarchy in particular. As I said a

18:57

minute ago, they've made the case

18:59

against Parliament for a decade. You know,

19:01

they've pretty well established that, look, Parliament

19:03

has no authority over us. We have

19:06

our own assemblies. They should govern. You

19:08

know, we're kind of sovereign. They've

19:11

always said up until 1776, but

19:14

George III is our monarch. So basically,

19:16

they say, look, the assembly of the House

19:18

of Burgesses, which is the assembly in Virginia,

19:21

is the equivalent of Parliament. It adopts legislation,

19:23

and the king approves it. Now

19:25

they're severing that tie with the king, which

19:28

means that long list of charges

19:30

in the Declaration of Independence focuses

19:33

mainly exclusively on the king. And

19:35

it's very, very personal. Every

19:38

one of the charges when you read them, it

19:40

says, he has, he's done this, he has not

19:42

done that. It's he, he, he, he, he. And

19:45

that's a reminder this document was intended to be

19:47

read aloud. So I would commend listeners to go

19:49

read the document, but try to read aloud in

19:51

your head. When you get to that bit, you

19:53

get to the end where he says it's the

19:55

bill of attain, they're basically against George

19:57

III. It's quite powerful and persuasive. rhetorically

20:00

because you get he, he, he, and

20:02

they're really making the case against the

20:05

king. Yeah, it's really interesting you

20:07

phrase it as a bit of a tanger then. The

20:10

only time I've seen a version of

20:12

the Declaration of Independence was when

20:14

the National Archives in Kew in

20:16

London did a treason exhibition and

20:18

it sort of looked at the development of treason,

20:20

say, from Edward III's creation of the treason

20:23

laws. A big high

20:25

point later on that I wasn't expecting was

20:27

the Declaration of Independence, which was very much

20:30

in the vein of Charles I, you

20:32

know, framing the king as a traitor

20:34

to a nation that was only just

20:36

coming into existence. And so you say

20:38

it's really, really personal effort to say

20:41

the king of Britain is

20:43

a traitor and therefore we don't want

20:45

him in charge of our new country.

20:47

That's it. It's not what they're essentially

20:49

saying is we're not leaving you,

20:51

you left us. You know,

20:53

as I say, we've got the rights of

20:55

Englishmen, we're upholding them. You know,

20:58

we are the true Britons, is their

21:00

claim. And it's George III who's left

21:02

us, not the other way around. In

21:05

that sense, it's a

21:07

conservative revolution in the

21:09

18th century sense in that it's backwards looking. They

21:12

are very, very mindful of the 17th

21:14

century precedents for what they're doing, the

21:16

glorious revolution but crucially before that, the

21:19

English Civil War. And

21:21

metaphorically, they're executing the king. They're

21:24

not literally doing it, of course, because they can. But

21:28

they're essentially saying we're not the rebels

21:30

here. You're the ones who've changed the

21:32

Constitution. We're upholding the Constitution. We're upholding

21:34

our understanding of the British Constitution. And

21:37

you've made it untenable here in America.

21:39

So we have to, you've forced us

21:41

to go our own way. In Jefferson's

21:43

original draft, and I think

21:45

we should talk a little bit about his

21:47

draft versus the one adopted by Congress, but

21:50

in his original draft, he's got language about

21:52

how sort of melodramatic, oh, we

21:54

might have been a great people together, but

21:56

you've changed things and they cut that rhetoric

21:58

out. But it's quite. Revealing actually

22:08

Have you ever wondered if the hanging gardens

22:10

of Babylon were actually real or

22:13

what made Alexander so great? Join

22:16

me Tristan Hughes twice a week every

22:18

week on the ancients from history hit

22:20

where I'm joined by leading academics and

22:22

best-selling authors and world-class archaeologists

22:24

to shine a light on

22:26

some of ancient history's most

22:28

fascinating questions Like who

22:31

built Stonehenge and why what

22:33

are the Dead Sea scrops and why are they so

22:36

valuable? And were the

22:38

Spartan warriors really as formidable as the

22:40

history books say join me

22:42

Tristan Hughes twice a week every week

22:44

on the ancients from history hit wherever

22:47

you get your podcasts Welcome

22:50

friends to the playful scratch from the California

22:52

lottery We've got a special guest today the

22:55

scratcher scratch master himself won won You've mastered

22:57

seven hundred and thirteen playful ways to scratch

22:59

impressive. How'd you do it? Well, I began

23:01

with a coin then try to get our

23:03

pick even used a cactus once I can

23:06

scratch with anything Even this mic right

23:08

here See

23:10

see well there you have it scratchers are fun

23:12

No matter how you scratch scratchers from the California

23:14

lottery a little play can make your day Please

23:17

play responsibly must be 18 years or older to purchase play

23:19

or claim your wedding will be one of the

23:21

happiest days of your life And Blue Nile can

23:23

help you celebrate it with a gift that will

23:25

last a lifetime Whether you're looking

23:28

for wedding bands a gift for your partner or

23:30

an unforgettable Thank you to

23:32

your bridesmaids Blue Nile offers a wide

23:34

assortment of jewelry of the highest quality

23:36

at the best price Plus expert guidance

23:38

to ensure you find the perfect piece

23:41

Experience the convenience of shopping Blue

23:43

Nile the original online jeweler since

23:45

1999 at Blue Nile calm Blue

23:47

Nile calm It's

23:58

interesting how they seem to have played

24:00

out the loyal opposition part,

24:03

you know, we are loyal to the crown,

24:05

but we'd like a few reforms, and

24:07

then they managed to phrase it as Britain

24:09

are cutting the ties. It's not actually America

24:12

cutting the ties and seeking to establish a

24:14

new country, you've sort of backed us into

24:16

a corner and forced us to do this

24:18

almost unwillingly. And as you say, it's weirdly

24:20

kind of conservative revolution when you compare it

24:22

to the French revolution that is not in

24:24

the too far distant future that is very

24:27

much like, no, we've had enough, we're sweeping

24:29

all of this away and we want something

24:31

new. It's kind of almost the opposite of

24:33

what the American revolution is saying. It's

24:36

a hoary old chestnut for student seminars, you

24:38

know, to compare the radicalism of the American

24:40

revolution to that of the French revolution. And

24:42

it is so for a reason, because these

24:45

are two very, very, I mean, they're related

24:48

events, but they're in their origins. They're

24:50

very, very different. And the Americans, at

24:52

least in the beginning, are, as

24:54

I say, very much looking back at

24:57

kind of 17th century precedents in contrast

24:59

to what we see in France. Jefferson's

25:01

draft, and then the final document, as

25:04

it's going through this process, what are

25:06

the main changes and why are things

25:08

taken out or added from what Jefferson

25:11

originally planned? So what happens is Jefferson's

25:13

working on this draft throughout June

25:15

of 1776. He's also doing

25:17

other committee work and so on. And

25:20

Congress eventually agrees on independence.

25:22

They don't get all 13

25:25

colonies to agree. They get 12 and New

25:29

York abstains. It's complicated. The

25:32

New York delegation favors independence, but they don't

25:34

feel that they can vote without the approval

25:36

of the New York provincial Congress, provincial government

25:39

in New York. So New York abstains. So

25:41

they have, they get 12 in favor of

25:43

independence. They vote on independence, formally on July

25:45

2nd, 1776. John

25:48

Adams famously says, July

25:50

2nd will forever be remembered as a

25:52

day that Americans will celebrate with fireworks

25:54

and parades and ice cream and all

25:56

this kind of thing. It's kind of

25:59

typical John Adams. and that he gets

26:01

it right but also spectacularly wrong. And then

26:03

what happens is Jefferson's draft

26:06

is presented to Congress and it spends two

26:09

days editing it. And so that's why the

26:11

4th of July is when the Declaration of

26:13

Independence is formally adopted. And that of course

26:15

is celebrated as in the way that Adams

26:18

suggested as Independence Day in the United States,

26:20

so not July 2nd. However, what

26:22

happened was Jefferson prepared his draft in

26:24

June, he submitted it to the Committee

26:26

of Five, which made really minimal changes.

26:29

And then for the two days between

26:31

July 2nd and July 4th, Congress

26:33

really edits Jefferson's draft. And

26:35

there are important differences. There's a story

26:38

that Jefferson tells in his autobiography that

26:41

he didn't like to be edited, none of us

26:43

like to be edited, but he's sitting, he sat

26:45

in Congress with Benjamin Franklin and he was very

26:47

agitated about the changes that Congress was making to

26:49

the document. And he felt that Congress was kind

26:52

of despoiling his work. And

26:54

Franklin told him a story about an

26:56

incident that allegedly happened in Philadelphia about

26:59

a hat maker who tried to get a

27:01

sign designed for his shop. And so first

27:03

it was like sort of, Matt Lewis, hat

27:05

maker, was on the, you know, and opened

27:07

these days and people came in and kept

27:09

changing. And eventually the sign is reduced to

27:11

just being a hat. And so Franklin tells

27:14

Jefferson this story to kind of reassure him

27:16

while he's going through the editing process. Congress

27:18

cut about 20% of Jefferson's text.

27:21

Some of it was for the better.

27:23

Some of it was for the worst.

27:26

The longest bit they cut concerned

27:28

the transatlantic slave trade. And I

27:30

think this is a really, really

27:32

interesting and important difference between the

27:34

document that Jefferson wrote and the

27:36

document that Congress adopted. Jefferson's clause

27:38

concerning the slave trade was in

27:40

that long list of charges against

27:42

George III. And it's the longest

27:44

of the charges that Jefferson wrote.

27:47

He blames George III for

27:49

the transatlantic slave trade. As history, this

27:51

isn't very compelling. George III was complicit

27:53

in the slave trade, but he certainly

27:55

didn't initiate Britain's participation in the slave

27:57

trade. Nor is he solely

28:00

responsible for. Let us not forget that

28:02

Jefferson enslaved approximately 200 people when he

28:05

wrote that condemnation. However,

28:07

what's really interesting about that clause,

28:09

I think, is in it, Jefferson

28:12

writes about George III

28:14

violating the rights and liberties of

28:16

a distant people. And the distant

28:18

people in this case are Africans

28:20

who are being victimized by

28:23

the transatlantic slave trade. What's

28:25

interesting there to me is, if we go back

28:27

to the beginning of the Declaration with

28:29

its assertion that all men are created equal

28:32

and endowed by their creator with certain unalienable

28:34

rights, and that among these are life, liberty,

28:36

and the pursuit of happiness, and

28:38

then we get further down in the document

28:40

and we see a direct reference to rights

28:42

and liberties being applied to Africans. It

28:45

changes the tenor of the document considerably.

28:48

In seminars with students, I'll say,

28:50

okay, how do we reconcile this

28:52

assertion of universal human equality

28:54

with the fact that 20% of the people

28:56

in these rebellious colonies

28:58

were enslaved? And one conclusion, or

29:00

one argument one could make is, well, yeah,

29:02

but he didn't mean, he wasn't applying it

29:05

to people of African descent, and everybody knew

29:07

that, so there was no need to say

29:09

that. And there's some merit to that argument,

29:12

except this clause suggests something quite

29:14

the contrary. He is aware that

29:16

Africans have the same rights and liberties as

29:19

Europeans who happen to live in America do.

29:21

And so it would have made it a

29:23

much, much more radical statement than it, I

29:25

mean, it's a radical statement, but a much

29:27

more radical statement than it was had Congress

29:30

included that language. It didn't, in part, because

29:32

there were people saying, oh, come on, look,

29:35

this isn't going to fly. And

29:38

according to Jefferson's autobiography that

29:40

Congress deferred to the interests

29:42

of two deep South colonies, Georgia, but

29:44

particularly South Carolina, in taking this language

29:46

out, because of course, one of the

29:48

purposes of the Declaration of Independence, as

29:50

I said a moment ago, is to

29:52

foster unity and help mobilize the population.

29:54

And not everybody wanted to go there.

29:56

So that clause gets cut out. It's

29:58

the most significant change. between

30:00

Jefferson's draft and the draft adopted by

30:03

Congress. They're worried, at least according to

30:05

Jefferson's telling, about losing the support of

30:07

South Carolina and Georgia. Now, there will

30:09

be an economic event. When they ban

30:11

the transatlantic slave trade, slaveholders in Virginia

30:13

in particular will benefit from that because

30:15

it creates an internal slave trade that

30:18

increases the value of their people who they

30:20

can then sell down to Mississippi and Alabama

30:23

because basically the slave population

30:25

in Virginia and Maryland is

30:27

too large. I mean, they've

30:29

got more slaves than they can support or they

30:31

can profit from. And so the abolition of

30:34

the slave trade, the transatlantic slave trade, will

30:36

benefit them financially. But I don't think that's

30:38

what they're thinking in 1776. I

30:41

think, and I've written a little bit about

30:43

this, and it's very hard to get students to accept

30:45

this. I think Jefferson's sincerely anti-slavery

30:47

in 1776. As

30:49

he gets older, he'll move away from it. He's still kind

30:52

of theoretically anti-slavery, but he keeps saying, well, they'll have to

30:54

do something about this in the future. But I think in

30:56

1776, he's pretty sincere

30:58

in that. Yeah, it's a missed opportunity, no doubt.

31:01

Because I guess it's always a difficult

31:03

juxtaposition to understand that idea of everybody

31:05

is entitled to freedom apart from the people who

31:07

aren't. It's always difficult to reconcile.

31:10

And it seems like there was an opportunity

31:12

there to have started

31:14

that conversation much, much earlier, this

31:16

lost opportunity chasing that need for unanimity.

31:19

Yeah, I think that's right. I think

31:21

that's right. Although it should be said,

31:23

the American Revolution does result in the

31:26

abolition of slavery in all the states,

31:29

new states, former colonies, north of

31:31

Maryland. So slavery was

31:33

unquestioned before the revolution. It's

31:35

not so in the new nation. Now,

31:38

I don't want to overstate the significance of

31:40

that because, of course, the vast majority of

31:42

enslaved people live south of Maryland, and

31:46

so it won't directly benefit them.

31:48

But also, the new United States

31:50

will vote to prohibit the transatlantic

31:52

slave trade in 1807, a

31:55

couple of weeks before Parliament does. So

31:57

there are important steps against slavery it,

32:00

but it is a missed opportunity. There's no question

32:02

about that. The last half full

32:05

version of this is, look, slavery is

32:07

unquestioned prior to this, apart

32:10

from a few radicals on both

32:12

sides of the Atlantic. And it's

32:14

now something that has to be defended.

32:16

And frankly, it's something Jefferson's embarrassed about

32:18

for the rest of his life. During

32:20

his tenure as ambassador to France, he's

32:23

acutely aware of how vulnerable he is

32:25

to criticism about slavery. And he's

32:27

embarrassed about it. Now, whether his embarrassment amounts to

32:29

much is debatable. But it's something

32:31

that has to be defended after 1776,

32:34

where it was largely unquestioned, not

32:36

exclusively, but largely unquestioned prior

32:39

to that. Interesting point at which the

32:41

conversation becomes a bit more intricate and detailed.

32:43

Once you declare all men are created equal,

32:45

you have to defend that position. I mean,

32:48

that raises, they didn't have to say that.

32:50

They could have just declared independence, but that's

32:52

what they say. And they're aware of this.

32:54

Samuel Johnson, the great English lexicographer, writes a

32:56

famous pamphlet in 1776 in

32:58

which he asked the question, why is

33:00

it we hear the loudest yelps for

33:02

liberty for the drivers of Negros? This

33:04

is not something that we thought of

33:06

later after the fact. They're aware of

33:08

this. And it is an intellectual

33:11

problem for them. It's a moral and

33:13

ethical problem for them. But it's also

33:15

an issue that enslaved people in particular

33:17

will not lie. And so they will

33:20

use this to undermine the institution. And

33:32

so I guess we need to get to

33:34

that famous moment, not John Adams, 2nd of

33:36

July. But the couple of days later, we've

33:38

I guess we've given away the date, but

33:40

I was going to ask kind of when

33:42

and where is the declaration signed and who

33:44

puts their name to it? Yeah, sorry, I

33:47

didn't mean to. No, no, it's fine. It'll

33:49

be a big surprise to anybody. So

33:51

it is formally adopted, the Texas formally

33:53

adopted on the 4th of July, 1776

33:55

in Carpenters Hall,

33:59

now called Independence in Philadelphia,

34:01

which is well worth a visit if you're

34:04

ever in the city of brotherly love. And

34:06

many, many listeners will be familiar. There's

34:08

a very famous painting, which is in the rotunda of

34:11

the Capitol in Washington by John

34:13

Trumbull of the signing of the Declaration of

34:15

Independence, which has everybody there. That

34:18

scene didn't happen because it took about a

34:20

month for everybody to get around to signing

34:22

the documents. So that kind of signing moment

34:24

that you get with the Committee of Five

34:26

in the center and all

34:29

the members of Congress sitting in

34:31

Independence Hall waiting to sign that

34:33

moment didn't happen like that. However,

34:36

it took about a month to sign and 56 men,

34:39

all men, of course, signed that document

34:41

over the course of a month. So

34:44

July 4th is the day it's adopted. There's no question

34:46

about that. And the text is agreed and the signing

34:48

begins, but it will take a little bit of time

34:50

for everybody to get around to signing it. In

34:53

the game, players will encounter that moment,

34:55

the signing of the Declaration of Independence.

34:57

They're there as a witness to that

35:00

and lots of other key moments in

35:02

the American Revolution. I wonder

35:05

then what happens in the immediate aftermath of

35:07

the signing of the Declaration of Independence? Presumably,

35:09

that's not kind of it. It's all over

35:11

now. We've declared independence and we're done. What

35:15

happens in the immediate aftermath to put that into force? Well,

35:18

there's no point in declaring something unless you tell people you're

35:20

doing it. That's what a declaration is, right? And

35:24

so what happens is they

35:26

send copies to Britain, but they also, copies

35:29

are printed and circulated around the declaration,

35:33

uses the phrase United States so we can talk about

35:35

the United States now, are circulated around the

35:37

putative United States. They're still not the United States yet. They

35:40

have to win their independence. But it's read before

35:42

the troops. So

35:45

the Continental Army, which was commanded by

35:47

George Washington, is in New York at

35:49

this point, preparing to

35:51

defend New York from an impending British

35:53

invasion. But Washington has

35:56

the text read to the troops on

35:58

July 9th. And

36:00

there's a famous scene which many

36:03

listeners will probably have seen different images of

36:05

them tearing down a statue

36:08

of George III from

36:10

the Bowling Green in New York. The

36:12

statue is decapitated, so this kind of ritual killing

36:15

of the king. It's melted

36:17

down for bullets, so there's a metaphor there.

36:19

They take this statue of George

36:21

III and they destroy it, and then they turn

36:23

it into bullets or some of it into bullets

36:25

that can be used to fight for independence. So

36:28

there's a kind of dramatic

36:30

metaphorical moment there. But

36:32

the hard work of actually winning independence

36:34

still has to go on. And

36:36

the war doesn't end until 1783. Much

36:41

of it goes badly for the patriots.

36:44

And independence isn't really confirmed until the

36:46

Peace of Paris of 1783. So

36:49

in the short term, this does mobilize

36:51

people, and it is propaganda, and it

36:53

will, in the medium term, eventually lead

36:56

to France joining the war effort,

36:58

as I suggested a few minutes ago. But

37:00

in the kind of immediate term, the

37:03

war went on. But everything's clear.

37:05

No longer are people saying, well, we're fighting the British

37:08

Army in the name of the king. They're now fighting

37:10

in the name of the United States. It sounds a

37:12

bit like you talked about

37:14

it being a multifunctional document and that

37:16

perhaps the most

37:19

immediate impact was in its use as

37:21

that diplomatic tool to say to other

37:23

countries, we are not going back. We

37:26

are here. And we would like your

37:28

support. Because then, as you said,

37:30

France, Dutch banks and things like that

37:32

feel confident enough to

37:34

help America, which will hopefully, from

37:37

the American point of view, tip the

37:39

balance of the war in their favor.

37:41

So it seems like that was the

37:43

perhaps the most immediate impact that it

37:45

had. It garnered support for the revolution.

37:47

That's right. I mean, I think the

37:49

diplomatic impact is in the

37:52

short term what's most important because it brings

37:54

France into the war and the

37:57

French intervention totally changes the nature of

37:59

the conflict. and evens

38:01

the playing field, or if anything

38:03

gives the rebels an advantage. So

38:05

there's no question. I think historically

38:07

the longer term impact is that

38:09

first paragraph and that mission statement

38:11

for the United States and that

38:13

justification for independence in

38:15

the name of human equality grounded

38:17

in actual rights. I wondered if we could

38:20

talk a little bit too about the continued

38:22

relevance of the Declaration of Independence, because it

38:24

feels a little bit like a

38:27

landlord has served an eviction notice on his tenant, the

38:29

tenant's gone and then the landlord just sits there keeping

38:31

reading the eviction notice again and again and again and

38:33

saying this is great. It

38:35

feels like something that was a one-off moment

38:37

in time served a purpose. Does

38:40

it still have relevance in America

38:42

today? Absolutely. So in 1848, when

38:45

the first big women's rights convention

38:47

was held in Seneca Falls in

38:49

New York, they adopted a version

38:51

of the Declaration of Independence saying

38:54

that all men and women were created equal. And

38:57

what we've seen throughout American

38:59

history is activists and

39:01

people actiontating for their rights always,

39:04

always invoke the Declaration of

39:06

Independence to do so, because

39:09

it's what Martin Luther King called a promissory

39:11

note. It's basically you said you were going

39:13

to do this, you've got to do it.

39:15

So King quotes it all the time, including on

39:17

the March on Washington. There's a

39:19

new book out by a really good

39:21

German scholar named Hannah Spahn, who's looked

39:24

at the way that black intellectuals in

39:26

the United States reframed the Declaration of

39:28

Independence during the 19th century in

39:30

opposition to slavery and take it

39:32

in directions that Jefferson himself probably

39:35

didn't intend. Lincoln invokes it

39:37

in opposition to slavery and to

39:39

justify taking action against slavery. So

39:42

throughout American history, it's continued to

39:44

be relevant. It's the touchstone. I

39:46

recently spent a year working at

39:48

Monticello, Thomas Jefferson's home that's now

39:51

a museum. And every year on

39:53

the Fourth of July in Virginia, they

39:55

have a naturalization ceremony there where new

39:57

citizens take the oath of allegiance.

40:00

to the country, and they do

40:02

it on the 4th of July in Jefferson's home

40:04

deliberately to make that connection with the Declaration of

40:06

Independence, and they read the Declaration of Independence that

40:08

day. In a couple years' time

40:10

in 2026, we will celebrate

40:12

the 250th anniversary of

40:15

the Declaration of Independence, and it

40:17

will be a massive, well, Americans

40:20

can't decide how to celebrate or commemorate that

40:22

moment because everything is political right now, but

40:24

something's gonna happen two years from now. Maybe

40:28

they'll read Jefferson's first draft, you never know.

40:31

That would be something. I mean, that would

40:33

be my preference. It's the director's cut. So

40:35

yeah, it still has continued relevance. It's not,

40:37

you know, it's not, it's certainly not a

40:40

forgotten document. It, along with the Constitution, but

40:42

when Americans frequently talk about the Constitution, they

40:44

mean the Bill of Rights are usually invoked,

40:46

and those are the two documents from the

40:49

kind of so-called founding year of the United

40:52

States that's continued to have contemporary relevance in

40:54

the United States. And I think sometimes

40:56

Americans make more of this than they

40:58

should, but there is a global impact to

41:01

it as well in that other countries, the

41:03

Harvard historian David Armitage has written about

41:05

this, other countries have used

41:07

the Declaration of Independence as a model

41:09

when they themselves declared independence, especially right

41:12

after the Second World War during decolonization

41:14

in the mid-20th century. Sometimes

41:17

that gets overstated, but I think it

41:19

does, it certainly has continued relevance. And

41:21

I guess as a medieval historian, my

41:23

mind immediately goes to Magna Carta and

41:25

the kind of immediate issues that that's

41:27

trying to address and that what it's

41:29

trying to deliver in the immediate term

41:31

versus this almost unforeseen long-term

41:33

effect that spreads out in all kinds of

41:35

directions that it was never really meant to.

41:38

Yeah, and people are always very good at

41:40

taking Magna Carta to mean things that it

41:42

never ever did mean, and misusing it for

41:44

all sorts of things. I

41:47

wondered if we could just ask a question

41:49

to end on. If you had the technology, if

41:51

you were an Assassin's Creed and you had the

41:53

animus that you could step into, what

41:56

moment during this process of

41:58

independence from Great Britain would

42:00

you like to be in the

42:02

room for? What moment would you

42:04

like to go back in time

42:06

and witness? Oh, that's a good

42:08

one. I think actually either the

42:10

moment when Jefferson presented

42:12

the Declaration to Congress and they

42:15

began debating it, or there's a

42:17

moment at the end

42:19

of the war in 1783, when

42:23

George Washington, this doesn't directly relate to

42:25

the Declaration of Independence, but George Washington

42:28

goes before Congress to

42:30

resign his commission. That's a crucial moment,

42:32

I think, in the history of the

42:34

United States, because that's when he willingly

42:36

gave up power. He willingly,

42:38

you know, he could have remained a military commander,

42:40

he could have become a man on horseback, and

42:43

he didn't do so. And when he goes

42:45

to resign his commission, I think that's incredibly

42:47

important. It's less dramatic

42:49

for Assassin's Creed. These are both kind

42:51

of civilian moments, but I think either

42:53

of those would be moments. I

42:56

would have liked to have witnessed. George III

42:58

is said to have said, he said to

43:00

the American painter, Benjamin West, who was president

43:02

of the Royal Academy, he, George III, asked

43:04

West what he thought George Washington was going

43:06

to do at the end of the war.

43:08

And West said, I think

43:10

he's going to give up power. And

43:12

George III is said to have said, but

43:15

according to West, if he does

43:17

that, he'll be the greatest man in the world. Nobody

43:19

can walk away from power. So I would have

43:21

liked to have seen that moment. I mean,

43:23

you get that a bit in Hamilton, don't you? Just to

43:25

bring it all the way back to Hamilton with George III

43:27

sort of saying, you know, giving up power, is that something

43:30

a person can do? Right. You

43:32

know, there's a lot of wisdom in

43:34

Hamilton. I'm just going to say that it's not a documentary.

43:36

So people who kind of pick nets and say, oh, what

43:38

about this, that or the other thing? As

43:41

a work of art, it's pretty amazing. I

43:44

think I would probably quite like to be

43:46

in the room on the 3rd of July

43:48

when people are pulling Jefferson's draft apart and

43:50

he's throwing an author's hissy fit about

43:54

what they're taking out. Yes. Imagine

43:56

having to sit in the room with reader number

43:58

two. Well,

44:01

your prose is being taken apart. Yeah. I feel

44:03

like I could nod in sympathy while he's complaining

44:05

about it. Well,

44:07

thank you so much for joining us, Frank. It's been fascinating to

44:09

get a bit closer to this document, a

44:12

bit under its skin and find out what was

44:14

going on around it and how it's taken on

44:16

this life of its own too. So thank you

44:18

so much for joining us. My

44:20

pleasure. The last thing I'd say is people

44:22

should read it because the text is actually

44:24

beautiful and it's not that long. But read

44:26

Jefferson's version. There you go. Two reading assignments

44:28

to take away. There you go. You

44:35

can find Frank's latest book, A Revolutionary

44:38

Friendship, wherever you get your books from. I

44:40

hope you've enjoyed this episode of Echoes of

44:42

History, a Ubisoft podcast brought to you by

44:45

History Hit. Next week, we're travelling

44:47

to the unlikely site of the shot heard

44:49

around the world and asking

44:51

just why two unassuming New

44:54

England towns became the most

44:56

significant places in the American

44:58

Revolution. Don't forget to

45:00

subscribe and follow Echoes of History wherever you get

45:02

your podcasts. And if you're enjoying it, you can

45:04

leave us a review too. I'll

45:07

see you next time among the Echoes

45:09

of History. Love

45:29

wasting money as a way to punish yourself because

45:31

your mother never showed you enough love as a

45:34

child? Whoa, easy there. Yeah. Applies

45:36

to online activations, requires port in

45:38

and auto pay. Customers activating in

45:40

stores may be charged non-refundable activation

45:42

fees. Welcome, friends, to the

45:44

playful scratch from the California Lottery. We've got

45:46

a special guest today, the Scratcher Scratchmaster himself,

45:48

Juan. Juan, you've mastered 713 playful ways to

45:51

scratch. Impressive.

45:53

How'd you do it? Well, I began with

45:55

a coin, then tried a guitar pick. I

45:57

even used a cactus once. I can scratch

45:59

with anything. Even this mic right here. See?

46:03

See? Well there you have it. Scratchers are fun

46:05

no matter how you scratch. Scratchers from the California

46:07

Lottery, a little play can make your day. Please

46:10

play responsibly. Must be 18 years or older to purchase

46:12

player claims.

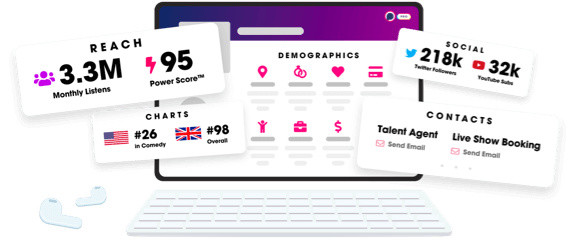

Unlock more with Podchaser Pro

- Audience Insights

- Contact Information

- Demographics

- Charts

- Sponsor History

- and More!

- Account

- Register

- Log In

- Find Friends

- Resources

- Help Center

- Blog

- API

Podchaser is the ultimate destination for podcast data, search, and discovery. Learn More

- © 2024 Podchaser, Inc.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

- Contact Us